The time has come - how I came to the decision to blog the Revo

The Revo Blog. Part 1 - background to Grenada

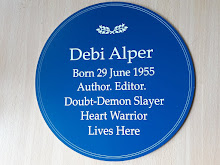

The Revo Blog. Part 2 - background to me

The Revo Blog. Part 3 - Feb-March 1982 (1 of 2)

The Revo Blog. Part 3a - why 'Revo'?

The Revo Blog. Part 4 - Feb-March 1982 (continued)

The Revo Blog. Part 5 - April 1982 - June 1983. London

The Revo Blog. Part 6 - June-Sept 1983. Sickness and signs

The Revo Blog. Part 7 - relationships

The Revo Blog. Part 7a - Faye's film

The Revo Blog. Part 8 - Sept - Oct 1983. Rumours

The Revo Blog. Part 9 - Oct 1983. The Last Days of the Revo

The Revo Blog. Part 10 - 19th October 1983. Coup

The Revo Blog. Part 11 - 20th October 1983. Curfew. Day 1

The Revo Blog. Part 12 - early morning 21st October 1983. Breaking curfew

The Revo Blog. Part 13 - curfew continues

The Revo Blog. Part 14 - 24th October 1983. 'Back to normal' day

The Revo Blog. Part 15 - 25th October 1983. Invasion - the first 2 hours

The Revo Blog. Part 15a - Faye's journey continues

The Revo Blog. Part 16 - 25th October 1983. War - the next 4 hours

The Revo Blog. Part 16a - photos

The Revo Blog. Part 17 - 25th October 1983 - midday onwards

The Revo Blog. Part 18 - 26th-27th October 1983 - the war continues

The Revo Blog. Part 19 - 28th-30th October 1983 - more war

Monday 31st October - another 'back to normal' day

Today all shops and businesses are supposed to open as normal. But what will 'normal' be under current circumstances?

We soon find out. After mentally preparing ourselves for the next stage, H, C and I go into town. As soon as we climb down from the bus in the market square, a film crew homes in on us. We're surprised, as we didn't think any international media would be around yet. But they are. And we're obviously conspicuous.

The main man tells us they're from ABC TV in the US and they got to the island after a gung ho perilous journey by boat. (We later find out that this guy is a freelancer who has a reputation for launching himself into global conflicts but then coming up with material so dire it can't be used.)

They interview us (I never found out if the interview was aired) but more importantly, they pay us $300 US for our first batch of films, which they promise they will send onto London after they have used them.

We walk on to Cable and Wireless, but there are still no international phone calls. At S's school, the signs are still up: No Bishop. No school. No work. It's a poignant reminder of just how little time has passed - it's less than two weeks since the high point of the Revo (people taking matters into their own hands and releasing Maurice from house arrest) was followed so swiftly by the ultimate low point (the coup).

While we're stocking up on fresh produce at the market, trucks bristling with GIs are coming down Market Hill. The brakes fail on one of them and it slews into a wall. The soldiers, not knowing the cause, leap from the truck, guns at the ready. A ripple of panic spreads through the square as people realise how volatile the situation still is and how easily it could descend again into violence and chaos.

While we're stocking up on fresh produce at the market, trucks bristling with GIs are coming down Market Hill. The brakes fail on one of them and it slews into a wall. The soldiers, not knowing the cause, leap from the truck, guns at the ready. A ripple of panic spreads through the square as people realise how volatile the situation still is and how easily it could descend again into violence and chaos. Back home, our friend N is there with her young son. At this point we realise how much of our personal experience of the war was the result of having no children of our own. In contrast, N and her kids had a terrible time. They had no food for days and spent much of the time hiding under a table.

Back home, our friend N is there with her young son. At this point we realise how much of our personal experience of the war was the result of having no children of our own. In contrast, N and her kids had a terrible time. They had no food for days and spent much of the time hiding under a table.Worse still, N's brother had been an inmate at the mental hospital. When it was bombed, he escaped and made his way through the bush to her yard at Happy Hill. Unsurprisingly, by the time he arrived he was crazier than ever. N went to the mental hospital today to ask for help and saw at least ten bodies banked up against the wall and more rotting in the bush and cane fields.

At about 3.30pm, we find the current is back on at last. H and I go to the Blue Danube for bread and find it well-stocked. On our way back, we see a sack lying in the road with bullets spilling from it. Feeling unable to ignore it, we stop a truck of Caribbean soldiers and point it out to them. At the Coke factory, we're stopped by GIs who are searching vehicles and bags.

Tuesday 1st November - defining 'normal'

The day starts with L and I having a huge argument. We're all still so stressed and traumatised, it's inevitable that this tension often spills over.

H and I go into St Georges to try to get gas. Town is crawling with soldiers and journalists, which is a new development. After a struggle, we manage to exchange our empty canister for a full one but are unable to get the new regulator we need for the cooker, so we still won't be able to use it.

This is a petty irritation compared to what happens next. We've suddenly panicked about the information we gave about our political background when we were hoping to set up the mobile library. We had gone into minute detail at the time, delighting in being able to lay all our radical cards on the Revo table. Now we're terrified about who may have access to those files.

We go along to the Ministry of National Mobilisation but we're told the guy we originally saw is out of the country and there's no one in charge. So where are the files? Are they still there lying on a desk or in a drawer? Or were they moved out - maybe to Butler House? In which case, were they destroyed? Or are they even now being read by the CIA ...?

As we make our way back home, we come across a road block at Springs and Belmont. We're told there is still fighting there. Spice Isle Radio confirms that there are still people resisting in the hills. We're also told again to stay inside from 8.00pm to 5.00am and for the first time since the invasion, this is described as a curfew.

And here's a weird one. It's announced that the PRA have three days in which to give up, after which they will be treated as deserters. Now what does that mean? What's the difference between being enemy soldiers and deserters? The suggestion seems to be that no prisoners will be taken after the deadline - instead, anyone captured will be executed.

So we've had a 'back to normal' day - just like after the original curfew.

And now we have a curfew - just like the original one.

And they're implying there will be executions.

We're beginning to question just how much things have changed.

Oh - and the US have admitted to their mistake in bombing the mental hospital.

Wednesday 2nd November - chronic

If you see the events of the last few weeks as a disease, we seem to have moved from an acute phase to a chronic one. And just like a physical illness, this stage has its own hideous characteristics.

H and I decide to try our luck at the Ministry of National Mobilisation again, hoping to track down our files. We're greeted by a stomach-churning sight. A GI is relaxing on the balcony, his feet up. The building has been taken over - by Psyops. Psychological Operations. Clinging onto a fragile thread of hope, we go to the old Ministry of Education. Maybe our files were transferred there? Predictably, this turns out to be a vain hope.

So what are the implications? If they have got hold of our info, will they come to pick us up? Interrogate us? Forcibly remove us from the country? This last seems the most appalling possibility and we talk about them having to drag us onto the plane kicking and screaming.

On the other hand, the information may have been destroyed or misplaced. We have no way of knowing ...

We walk to Queen's Park but there's nothing much new happening there. At Tempe Junction, we're stopped by paratroopers from the 82nd Airborne. There's a Russian tank up the road on fire with 17 gallons of gas and 200 rounds of live ammunition on board. While we wait for the fire to be put out, the paras chat to us quite amiably. Another has the inevitable 'Better Dead than Red' slogan stenciled on his helmet.

They tell us Hudson Austin was found at St Paul's and that lists were found at a 'house of the People's Rebellious Group or whatever they're called'. They also say that they are leaving on Saturday but will be replaced. They reckon the troops are 'here to stay'.

Meanwhile, there are still no international phone calls, commercial flights or post. And Spice Isle Radio announces a State of Emergency: no torches, drums, noise or firearms. Punishment will be $500 fine or six months in prison or both. The list of things forbidden is eclectic enough to be unsettling and maintain heightened levels of anxiety. Firearms you can understand, but torches? Drums? And just how much noise is too much?

Yes. This is 'normal'.

Tomorrow won't be. We're going to go to the crazy house with N ...

4 comments:

Debi the clarity with which you write is striking. The cold penning of your words creates, I think, a deeper chill than any emotive words could possibly do justice to.

With elections on Wednesday, afterI'm left thinking about what has happened and is happening here, and what may happen in the future...

Wow Debi I've just been catching up with the blog - fascinating and intense. It's wonderful to see your photos, and I was particularly stuck by your 'lists' ('we hear.../ PC says...') which show just how little you could rely on any single piece of information, and by the young Americans taking their cue from film. The way that 'normal' life continues even in crisis reminds me of some accounts I have read of concentration camps, where even in the midst of such horror inmates had 'good' and 'bad' days - very human, I guess. I think the line that really sums it up is the one from your diary - 'Now is forever'.

Your astute comment says as much about you as it does about what I have written, Lowkey. Thanks!

Post a Comment