The time has come - how I came to the decision to blog the Revo

The Revo Blog. Part 1 - background to Grenada

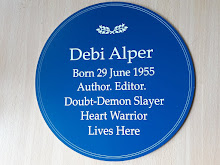

The Revo Blog. Part 2 - background to me

The Revo Blog. Part 3 - Feb-March 1982 (1 of 2)

The Revo Blog. Part 3a - why 'Revo'?

The Revo Blog. Part 4 - Feb-March 1982 (continued)

The Revo Blog. Part 5 - April 1982 - June 1983. London

The Revo Blog. Part 6 - June-Sept 1983. Sickness and signs

The Revo Blog. Part 7 - relationships

The Revo Blog. Part 7a - Faye's film

The Revo Blog. Part 8 - Sept - Oct 1983. Rumours

The Revo Blog. Part 9 - Oct 1983. The Last Days of the Revo

The Revo Blog. Part 10 - 19th October 1983. Coup

The Revo Blog. Part 11 - 20th October 1983. Curfew. Day 1

The Revo Blog. Part 12 - early morning 21st October. Breaking curfew

The Revo Blog. Part 13 - curfew continues

Monday 24th October. 'Back to normal' day.

6.00 am Radio Free Grenada. There's a broadcast from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs saying there are now two ships in Grenada's territorial waters but no invasion as yet. I can hear more than a hint of panic in their urgent pacifying claims that foreigners can come and go as they please and the Revolutionary Military Council has no desire to rule Grenada. Just words.

Today's the day when life is supposed to return to normal. Shops, offices and all other workplaces will be open and everything apart from schools should operate as usual.

As though the Revo hadn't imploded five days ago. As though the people's chosen leaders weren't all dead. As though those same people hadn't been slaughtered, terrorised, lied to and imprisoned throughout the last week.

What might today hold in store? With no opportunity for organising during the curfew, will there be a spontaneous uprising? If so, how will it be dealt with? Will the PRA turn their guns on their own people? Or will elements within the army, loyal to the true Revo, rise up against their masters? Either way, it's impossible to imagine a scenario that doesn't consist of Grenadian killing Grenadian.

Unless the Americans invade. And if they do, will people resist? Or will they welcome the invaders as a preferable alternative to a bloody civil war?

And how will the bombs discriminate between those who resist and those who accept?

It's impossible to know what to hope for. All we can do is live it.

One thing's for sure. Whatever the day holds we have to get out of the yard where we've been confined for the last four days. As a first foray into the outside world, L and I go to Blue Danube, the little shop on the hill leading to town. Here at least, it seems the spirit of the Revo lives on. Though supplies are dwindling fast, the shop owner is actually lowering prices - not cashing in on people's desperation as might happen elsewhere. When L and I don't have enough money to buy everything we need, the owner allows us to leave with the shopping and owe him the balance.

Even though he can't know if we'll be alive to pay it. And we can't know if he'll be alive to receive it.

I've always believed you should try to live in the moment, but never has there been so little choice about it.

PC comes round soon after L and I arrive home. He tells us that when Maurice was freed from house arrest he appeared weak and confused, wearing only underpants and unable to walk without assistance - let alone carry a gun. Had he been drugged?

The news from radio 610 is that Amnesty International have sent a cable to Hudson Austin asking for a public inquiry into the deaths of Maurice and the others and the arrests of Radix and Alistair Hughes.

H and I go together into town as she's feeling strong enough now. There are long queues for kerosene, calor gas and food. Panic buying means that the shops are emptying really fast. A crowd gathers outside Lacqua Funeral Home as two body bags are brought in. The bank is packed but we manage to draw some cash.

Not without trepidation, we head up to the hospital as we need to get a blood test form for H. There's an eerie sense of calm, as there was on the day of the coup. It's hard to believe that less than a week ago a slaughter took place a few yards up the hill at the fort. We're told that five women have been admitted with bullet wounds but the men's ward is full. We're not allowed into the wards to see for ourselves, but are told that last night the private block was emptied out and all the staff were sent back to the nurses' home - presumably for them to get as much rest as possible. With no one to answer their calls, patients lay in their beds all night and bawled for help that wouldn't come.

Tearing ourselves away, we next head for Cable and Wireless to call home. At least the phone lines are operating. Mum sounds freaked, though relieved to hear my voice. But she is furious when I tell her I have no intention to leave. I know how hard it must be for her but beg her to understand that I can't just wave my passport and run away.

Returning to Tempe, we meet PC again. He tells us he's found out his daughter's foot was mashed at the fort. We give him $20 EC to buy milk and medicine.

L has been into the country to St David's to check on his aunts. He returns with bags of fresh produce which are most welcome but the bad news is that he got into a huge row with a guy over coral and money. Everyone is so stressed and tempers are frayed. It's inevitable that tensions boil over and it feels like the potential for violence of one kind or another is just a breath away.

But with time having shrunk to the immediate here and now and still no idea what might happen next, we can't afford to keep still and feel the need to get as much done as we possibly can, while we can. L and I return to town with the empty gas cylinder but no one seems to think we'll be able to get gas. We're obsessing about the cylinder - it has assumed vital importance, since almost everything else seems to be out of our control. We meet P and leave the cylinder with him before returning to Tempe again.

Everywhere we go - locally, in town, on the buses - people are ranting against the RMC and don't seem to care who hears them. The mood is one of anger rather than fear. There appears to be almost total unity - pro Maurice and anti RMC.

There isn't a particularly large military presence on the streets and it really does feel bizarrely like life is carrying on pretty much as usual. Even up at the hospital and the fort (which is on the same hill) there's no obvious sense of the trauma of the last week or fear of what is to come. It's surreal and I have no way of knowing if this is how people always react when they're in deep shock. Maybe it's just the urge to survive.

Along the esplanade there are a couple of slightly antiquated looking guns pointing out to sea, each surrounded by four or five sandbags. They look like props from an old movie and when you think what they are supposed to be defending us against, they add to the surreal feeling that this can't be real.

When we reach back home, C is there. Poor C had gone to Carriacou, Grenada's tiny sister island, on the morning of the coup and so spent the whole curfew there on her own.

When she had arrived on the 19th, she was greeted by a demonstration by local schoolchildren carrying placards: No Bishop. No School and several others specifically anti-Coard. Later there was another demonstration by older youths, No Bishop. No Work.

There was joyous dancing in the streets when the news filtered through that Maurice had been released and a motorcade drove through town, horns blaring and people cheering. Then RFG went off the air. Reports from regional stations were confused but it was clear that there had been extreme violence. C says the mood became very subdued, with people clustered round radios in the streets, waiting to hear what had happened a short distance away across the water.

Then, when the terrible confirmation of the coup was announced that evening, C says there was utter silence. Over the next four days the curfew didn't really operate in Carriacou, where there were only five soldiers on the whole island, and apparently not a single volunteer responded to the call for people to join the militia.

I can't imagine how terrible it must have been for C during those dread-filled days, totally isolated, knowing no one at all in Carriacou and alone with her grief and fear. However bad your own suffering, you can always find people who have it worse.

6.00 pm RFG - apparently Guyana opposed Grenada's suspension from the OECS, which means the decision is not binding. The broadcast also says that a contingent of soldiers left Jamaica on Saturday night - which was before the decision to invade was allegedly made.

And once again, this all feels surreal. They're not focusing on the same things as their listeners. It's clear their agenda has switched to a defensive stance projected outwards to try to avoid invasion, whereas everyone else knows there's unfinished business right here on the island.

P returns from town with the empty cylinder - there's no gas to be had anywhere. With only a partial cylinder left between us and C, we're going to have to be careful to eke it out by cooking communally and with care. W also arrives and now we're all together again. He told me a couple of days ago about a Tempe man who had an illegal gun. Today W saw this man in town - in uniform. He had been given a choice: to go to prison or join the army. They must be desperate indeed if he's typical of the kind of person they are relying on to defend the island against invasion.

And that's the end of 'back to normal' day. Only it feels like a day when we ran around like headless chickens trying to second guess what would happen next and preparing as much as possible for something we couldn't predict or even imagine. C is back with us, and that's the most important thing. At least we are all together now to face the next stage. Whatever it will be.

We don't have to wait long to find out.

That night L wakes up with dreadful stomach pains. From 3.00 am onwards, I pad backwards and forwards between the kitchen and the bedroom, massaging his belly, boiling up bush tea and worrying about how much gas I'm using.

Something is niggling on the very periphery of my consciousness but I can't work out what it is. There are so many things that are 'not right'. I'm anxious and half-asleep and I can't focus on what this particular niggle might be.

Soon after 5.00 am, H emerges from her room.

'Have you heard it?' she says.

'Heard what?'

'The plane - circling high overhead. It's been buzzing faintly all night.'

Image from BBC today

And now I identify the niggle and know its significance and why I'd been blocking on it. With tiny Pearls airport on the opposite side of the island, we never hear airplanes overhead. Yet H is right. This one has been circling for hours. Grenada has no air force, so this can mean only one thing.We're about to be invaded.

3 comments:

Blimey. I know it's kind of awful considering how personal this all is to you, but I'm very eager to know what happens next.

Masterfully told, Debi. The tension and anticipation are almost unbearable. How much more so it must have been for those who were actually there I can only imagine.

Re the real/surreal issue: Going through the motions of the normal probably helps keep people from going over the edge in situations that are horrendously not normal.

The tension never lets up, Clare.

Liane - I expect you're right. I have nothing to compare it to so don't know how 'normal' our reactions were. All I know is that the feeling of unreality is not what I would have expected. Unless you live it, you can't know how you would react.

Post a Comment