The time has come - how I came to the decision to blog the Revo

The Revo Blog. Part 1 - background to Grenada

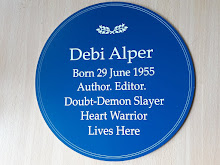

The Revo Blog. Part 2 - background to me

The Revo Blog. Part 3 - Feb-March 1982 (1 of 2)

The Revo Blog. Part 3a - why 'Revo'?

The Revo Blog. Part 4 - Feb-March 1982 (continued)

The Revo Blog. Part 5 - April 1982 - June 1983. London

The Revo Blog. Part 6 - June-Sept 1983. Sickness and signs

The Revo Blog. Part 7 - relationships

The Revo Blog. Part 7a - Faye's film

The Revo Blog. Part 8 - Sept - Oct 1983. Rumours

The Revo Blog. Part 9 - Oct 1983. The Last Days of the Revo

The Revo Blog. Part 10 - 19th October 1983. Coup

The Revo Blog. Part 11 - 20th October 1983. Curfew. Day 1

The Revo Blog. Part 12 - early morning 21st October 1983. Breaking curfew

The Revo Blog. Part 13 - curfew continues

The Revo Blog. Part 14 - 24th October 1983. 'Back to normal' day

The Revo Blog. Part 15 - 25th October 1983. Invasion - the first 2 hours

The Revo Blog. Part 15a - Faye's journey continues

The Revo Blog. Part 16 - 25th October 1983. War - the next 4 hours

The Revo Blog. Part 16a - photos

The Revo Blog. Part 17 - 25th October 1983 - midday onwards

26th-27th October - the war continues

The night passes without incident. We've survived our first day of war. From 1.00 am onwards, there are jets circling overhead constantly, but otherwise it's comparatively quiet with no direct combat.

All that changes at 5.00 am. Just before dawn, the still-dark sky is ripped apart by phosphorescent flares and there's an immediate response as anti-aircraft guns blast in response. We hear three loud blasts as bombs go off in the distance. Tanks are grinding up the hill and there's firing immediately around our house. H emerges from her room to say she could hear PRA in the bush beneath her window and then she saw one of them running out from the trees.

We all gather together again and switch the radio on, aware that we have limited battery life and there's still no current, but we have to prepare ourselves to face whatever this next day will bring.

Trinidad radio tells us that the US are sending reinforcements.

Incredible. They must be meeting more resistance than they anticipated. But this is tinged with terrible sadness as we know that there can't be that many people prepared to lay down their lives for a revolution that no longer exists. Once again, we reflect how different the scene would have been if the invasion had happened before Maurice and the others were murdered.

Since the coup, invasion is seen as preferable to the alternative. That, more than any other single factor, is a measure of the depths of the crime committed at the fort on the 19th.

Throughout the day, the fighting continues. Sometimes in the distance and sometimes frighteningly close by with helicopters, jets, tanks and anti-aircraft fire. You never know if each lull could signal the end of combat or if things could get still worse.

Excerpt from my diary: The 'present' has shrunk to RIGHT NOW. NOW IS FOREVER.

We still have no current and are operating the radio on batteries. At some point, we decide to drink the water. This seems incredible looking back now but in reality there's little choice and it's a risk we decide we have to take. We feel our fate is not in our own hands anyway and what will be, will be.

As yesterday, we receive frequent visits and updates from PC.

PC says there's fighting on the streets of Tempe.

PC says the loud blasts are from the camp behind the Lord Chief Justice's house.

PC says he's been to Queens Park, where the US troops are based.

PC says we just need the inevitable end to come and he led the GIs to a hidden arms cache.

PC says many of the PRA are stripping off their uniforms and melting into the bush.

PC says the prison has been bombed and the Mongoose Men (hated and feared as the henchman of Gairy, the dictator ousted by the Revo) are out on the streets.

PC says Hudson Austin has been located at Sans Souci, Tempe junction. There are rumours he's holding hostages.

PC says there's lots of looting going on in town.

Every detail he imparts has significance beyond the obvious. One thing is clear. Tempe is in a small geological bowl surrounded by hills - the Governor General's house, the Lord Chief Justice's house, Richmond Hill with the forts and the prison, Mt Parnassus ... No wonder the fighting is so close by.

And yet - in spite of this - it's impossible to stay huddled in our yard now that the first day is over and we don't know how long this war will last. In the late afternoon, H and I go for a walk down Tempe road during one of the lulls. We reach Midway, where there's a small group of people liming. As we walk a little further, there's a blast and smoke rises up from beside the river - just yards away from us.

It's amazing how quickly we've become desensitised to the dangers. A couple of days ago, that one blast would have had us scurrying for shelter in panic. Now we just stop in the road and say it might be better not to go any further. We wander back and join the limers. While we're sitting there, perched on the wall, we're passed by vanloads of people on their way to Queens Park to see the US troops. P returns, having made a trip into town and tells us that NCB, Huggins and all the tourist shops have been looted, with one bar completely smashed in by an armoured car.

Thursday 27th October

There's sporadic fighting throughout the night but now that we've become accustomed to the concept of war (how fast that happened!) each day is different.

On this third day, PC comes round at 7.00 am accompanied by his young daughter, R. H and I walk with them to Tempe junction. The Shell garage on River Road has been razed and there's damage to the nylon factory. We come across a dismantled PRA anti-aircraft gun in the bush by the road.

There are lots of people on the streets and vehicles pass, bearing white flags. Our hearts ache as we note that the general mood is one of victory. I think it must be relief that the end must surely be in sight and people are euphoric to have survived through this last week when one trauma has followed another with no respite.

There are lots of people on the streets and vehicles pass, bearing white flags. Our hearts ache as we note that the general mood is one of victory. I think it must be relief that the end must surely be in sight and people are euphoric to have survived through this last week when one trauma has followed another with no respite. But now there are new horrors to assimilate. We're introduced to three men - and are told they are Mongoose Men, escaped from the prison. Then there's another man we meet - and our stomachs lurch when we hear he is the counter revolutionary charged with planting the bomb in Queens Park that killed three women, back in 1980. And a Rasta is pointed out to us as having recently killed a priest.

But now there are new horrors to assimilate. We're introduced to three men - and are told they are Mongoose Men, escaped from the prison. Then there's another man we meet - and our stomachs lurch when we hear he is the counter revolutionary charged with planting the bomb in Queens Park that killed three women, back in 1980. And a Rasta is pointed out to us as having recently killed a priest.Whereas we've always felt in Grenada that everyone we meet is likely to be on the same side, that is patently no longer the case. It's not only the US troops we have to fear. We resolve to watch and smile and take things in, but keep our mouths firmly shut.

If anything, the soldiers we meet are anything but frightening. Most of them are very young and many of them seem scared - and also confused.

'Who are we supposed to be fighting?' one of them asks in a plaintive voice. 'We thought it was the Grenadians, but ....'

He looks round helplessly at the unthreatening people wandering along the road.

'Is it the Cubans? We just don't know ...'

The lack of certainty has clearly disorientated them.

One of them even asks us how long we think they'll be here. Like we would know ...

There's one soldier who has 'Better Dead than Red' stencilled on his helmet and I have to stifle the urge to giggle. Doesn't he know how much of a walking cliche he is? But then I realise. Just as much as our survival mechanism has often consisted of seeing this all as a movie, this must be true for them too.

There's one soldier who has 'Better Dead than Red' stencilled on his helmet and I have to stifle the urge to giggle. Doesn't he know how much of a walking cliche he is? But then I realise. Just as much as our survival mechanism has often consisted of seeing this all as a movie, this must be true for them too.Queens Park is a hive of activity. The field is filled with rows of tanks, armoured cars and personnel carriers - all the paraphernalia of war.

Choppers take off and land, supplies are shifted, soldiers hang out. H and I zap into our own new roles and make light conversation with the GIs who tell us they're from 8th Battalion, 2nd Division.

We walk round and onto the esplanade. The mood is heavier here. There's large scale looting, with some committed to getting as much as they can and others angrily berating them. Drivers whoosh past in stolen government vehicles. Nothing is off limits.

We walk round and onto the esplanade. The mood is heavier here. There's large scale looting, with some committed to getting as much as they can and others angrily berating them. Drivers whoosh past in stolen government vehicles. Nothing is off limits.As we wander round town, we see the bombed remains of Butler House, scene of so many happy parties in the old days. All of the banks and most of the shops have been broken into.

And then I see something that penetrates the information-gathering shell I have taken on and makes me want to break down then and there and weep. A group of people are tearing up Revo books in rage. Maybe these are people who were always against the Revo. But I have a terrible fear that for some, the hideous experiences of the last week may have become associated with the Revo itself and not with the actions of Coard and his cohorts.

We walk into the Ghetto, where the mood toward us is cool. We're relieved to find we don't appear to be viewed with suspicion. We sit and smoke and reason for a while. The vibe here is split with some of the Rastas expressing fears that Grenada could become more like Texas or Jamaica. Several of them say they're convinced Coard is working directly for the CIA and I seize on this possibility.

It's so much easier to believe than what in my heart of hearts I know to be true - that the Revo was destroyed from within. And if we focus instead on the traditional enemy - the CIA - we fail to learn the terrible lessons and Maurice and the others will have died in vain.

We meet people who began by fighting but then could see how little point there was and so backed off. As we walk up behind the Ghetto, we see that many of the houses here have been damaged and we see the charred patch on the ground where the chopper came down in Tanteen playing field. At the top of the hill, there's an abandoned PRA tank, with people busy syphoning off the petrol.

Back in Tempe, we see more evidence of people's determination to bring the war to a quick conclusion. S has organised search parties and has already found four PRA and delivered them to the US troops in Queens Park. Poeple have been evacuated from the houses round Tempe quarry so the US can flush out the PRA reputed to be holed up there.

Back in Tempe, we see more evidence of people's determination to bring the war to a quick conclusion. S has organised search parties and has already found four PRA and delivered them to the US troops in Queens Park. Poeple have been evacuated from the houses round Tempe quarry so the US can flush out the PRA reputed to be holed up there.And there are more contradictions when we get back home. W has looted a turtle back and while C and I are arguing with him about it, P arrives. As well as cigarettes and soap, he has taken the framed portrait of Maurice from Grencraft. We don't know what to say. Overwhelming sadness bubbles up at the poignant symbolism.

Suddenly, L arrives, pouring with sweat and coated in mud and accompanied by three other guys. They're carrying sacks of flour, tools and god knows what else, looted from a military camp. This isn't as bad as looting from shops, I guess, but I'm concerned that it's all being shared out and distributed from our verandah.

But the bottom line is that Grenada is their home and, as outsiders, we have no right to take the moral high ground and say what is or isn't acceptable. It's the steepest of learning curves.

Another terrifying development. We've just heard the US troops have arrested J, a friend from Tempe. But he's not even in the PRA ...

That night there's heavy fighting again. If war is a disease, we've moved from an acute to a chronic stage with occasional flare ups to remind us it's still far from over.

But war is manmade and has nothing on Mother Nature. There's a massive storm during the night and we derive a sense of satisfaction that the lightning is brighter than the phosphorescent flares and the thunder outblasts the bombs.