Can't believe I've done it! I'm on a writing retreat and an unexpected side effect is that my lovely host has persuaded me to join Twitter.

So now, as well as this neglected blog, a hideously out-of-date website, a very busy Facebook page and various forums, I have a new distraction.

I blame the gin.

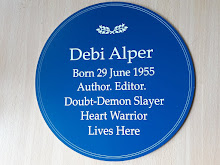

If this means anything to you, check me out at @DebiAlper

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Thursday, May 19, 2011

The People Collector

Authors are often asked where we get our ideas and characters from. Friends and relatives have even been known to be nervous that fictional characters might be based on them. I was shocked and saddened when my sister-in-law asked if the sister-in-law in my Nirvana series was supposed to be her.

The fictional version is shallow and snobbish. Surely, my real sister-in-law didn't think I see her in this way. (I really don't.) And, even if I did, did she believe I would abuse our relationship by sharing my negative perceptions of her with the world?

The truth is, I do collect characters, but no one who knows me would ever be able to recognise themselves in my books. Most of my inspiration comes from people I encounter but know nothing about. My favourite people-spotting opportunities come from bus journeys.

I always sit on the top deck by the window. I look down on shoppers, workers, wanderers, seeing them from a different angle to the norm. Where is she going? What does his home look like? Where does she work? What's their story? I peep into uncurtained first floor windows to get a fleeting glimpse of people's internal landscapes; odd ornaments on the window sill, a torn sheet instead of a curtain, piles of old newspapers, a row of polished trophies ...

I can give full rein to my imagination. The stories I weave most likely bear no resemblance to the truth. Or do they? They might be eerily accurate. But it doesn't matter one way or another, because the person I've observed will never know they've inspired a story.

A little closer to the bounds of propriety, I like to eavesdrop on conversations. Take last week, for example. In the seat behind me, a teenage girl was talking about the tradition in her private school of playing pranks when pupils leave at the end of Year 11. Her personal favourite, she told her unseen companion, was when a group of pupils got hold of a cow. (At great expense, she added.) Cows, she went on to say, can go up stairs, but not down. Somehow, they managed to smuggle the animal into the school and up the stairs, where they abandoned it. With no alternative, the school was forced to arrange for the poor (and, no doubt, distressed) beast to be rescued by helicopter. Presumably, at further great expense.

The girl moved on to talking about her plans for the summer: a week at the family villa in France followed by a journey south for an extended stay in St Tropez.

I resisted the urge to turn round, so I never saw what she looked like. But she was speaking loud enough for me to hear (which is saying something) and appeared to have no concept of the extent of her privilege, or that most of her fellow travellers might inhabit a very different universe.

That girl might appear as a cameo in a story some time. The challenge for me would be to lift her beyond stereotype. I was so engrossed that it took me a while to realise I was on the wrong bus.

The next bus (the right one this time) provided contrasting, but equally fertile, ground for harvesting characters. Two middle-aged Jamaican men were discussing the iniquitous cost of a TV licence, which both agreed was a struggle for poor people to afford. From there, they moved on to talk about international politics and the subtle differences in the way racism is manifested in the US and the historical reasons for those differences. Then it was current affairs: whether the authorities in Pakistan had been aware of Bin Laden's whereabouts. By the time I left the bus, they'd become involved in a complex discourse on the nature of fear.

Rich pickings for a novelist: these men and their (possible) personal stories; any of the subjects they touched on; the rhythms and patterns of their speech; the timbre of their voices ... In many ways, the sheer depth of the insights these men gave means that they would be far easier for me to bring to life in a fictional setting than the girl would be, lifting them beyond the risk of cliche and stereotype.

So, whether you're sitting on the top of a bus, shopping in the supermarket, walking on the streets, wandering in the park, queueing at the post office ... keep your eyes and ears open.

And if you're not a novelist, be aware that the person in the next seat might be watching you and listening to your words, storing them away for future use.

So, do you reckon this is OK? Or is it a form of identity theft? And does it matter one way or the other?

The fictional version is shallow and snobbish. Surely, my real sister-in-law didn't think I see her in this way. (I really don't.) And, even if I did, did she believe I would abuse our relationship by sharing my negative perceptions of her with the world?

The truth is, I do collect characters, but no one who knows me would ever be able to recognise themselves in my books. Most of my inspiration comes from people I encounter but know nothing about. My favourite people-spotting opportunities come from bus journeys.

I always sit on the top deck by the window. I look down on shoppers, workers, wanderers, seeing them from a different angle to the norm. Where is she going? What does his home look like? Where does she work? What's their story? I peep into uncurtained first floor windows to get a fleeting glimpse of people's internal landscapes; odd ornaments on the window sill, a torn sheet instead of a curtain, piles of old newspapers, a row of polished trophies ...

I can give full rein to my imagination. The stories I weave most likely bear no resemblance to the truth. Or do they? They might be eerily accurate. But it doesn't matter one way or another, because the person I've observed will never know they've inspired a story.

A little closer to the bounds of propriety, I like to eavesdrop on conversations. Take last week, for example. In the seat behind me, a teenage girl was talking about the tradition in her private school of playing pranks when pupils leave at the end of Year 11. Her personal favourite, she told her unseen companion, was when a group of pupils got hold of a cow. (At great expense, she added.) Cows, she went on to say, can go up stairs, but not down. Somehow, they managed to smuggle the animal into the school and up the stairs, where they abandoned it. With no alternative, the school was forced to arrange for the poor (and, no doubt, distressed) beast to be rescued by helicopter. Presumably, at further great expense.

The girl moved on to talking about her plans for the summer: a week at the family villa in France followed by a journey south for an extended stay in St Tropez.

I resisted the urge to turn round, so I never saw what she looked like. But she was speaking loud enough for me to hear (which is saying something) and appeared to have no concept of the extent of her privilege, or that most of her fellow travellers might inhabit a very different universe.

That girl might appear as a cameo in a story some time. The challenge for me would be to lift her beyond stereotype. I was so engrossed that it took me a while to realise I was on the wrong bus.

The next bus (the right one this time) provided contrasting, but equally fertile, ground for harvesting characters. Two middle-aged Jamaican men were discussing the iniquitous cost of a TV licence, which both agreed was a struggle for poor people to afford. From there, they moved on to talk about international politics and the subtle differences in the way racism is manifested in the US and the historical reasons for those differences. Then it was current affairs: whether the authorities in Pakistan had been aware of Bin Laden's whereabouts. By the time I left the bus, they'd become involved in a complex discourse on the nature of fear.

Rich pickings for a novelist: these men and their (possible) personal stories; any of the subjects they touched on; the rhythms and patterns of their speech; the timbre of their voices ... In many ways, the sheer depth of the insights these men gave means that they would be far easier for me to bring to life in a fictional setting than the girl would be, lifting them beyond the risk of cliche and stereotype.

So, whether you're sitting on the top of a bus, shopping in the supermarket, walking on the streets, wandering in the park, queueing at the post office ... keep your eyes and ears open.

And if you're not a novelist, be aware that the person in the next seat might be watching you and listening to your words, storing them away for future use.

So, do you reckon this is OK? Or is it a form of identity theft? And does it matter one way or the other?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)